Published by permission from the Charles E. Fraser Estate, with editorial assistance from Laura Lawton Fraser.

From my desk across the creek, I continue the story of Hilton Head Island’s first decade of development. All of the factual information I have sourced for this article is from a speech written by Laura Lawton Fraser, daughter of Sea Pines Resort developer Charles E. Fraser, which she gave to the Masters in Real Estate Class at Clemson University in 2014. Her insight comes from a deeply personal account of being raised in Sea Pines and learning by her father’s side.

I previously described how Charles E. Fraser had set his heart on developing the island. He left what could have been a lucrative, lifelong career in law to pursue a dream. His dream was to turn this mosquito-infested, swamp water-infused maritime forest known as Hilton Head Island into a sun soaked, warm breeze paradise for visitors and locals alike to live, work and play. He dreamed large.

The first real line of business was setting legal principles into place for what his dream community would look like. He wrote a 150-page document of land use covenants, the first of its kind, detailing what could be built on the land – and what could not. Prior to Charles’ forethought on this subject, these types of principles had not been outlined in any other community. He had learned of this British concept, however, while studying at Yale Law School.

In today’s world, no one would dream of creating a community without land use covenants. Charles was far ahead of his time.

He was concerned about making a profit, but more importantly, he cared deeply for the island and for being a good steward of the earth. He wanted to ensure that the development of the island wouldn’t interfere with the beauty of the surrounding landscape. He spent significant time and money to get the foundation just right before building. He pledged from the beginning to preserve 1,200 acres as a nature preserve, without gaining any tax benefits.

The first project Charles set forth was the building of the William Hilton Inn, the first luxury accommodation on the island. (The Marriott Grand Ocean is now located on the original site of the Inn.)

The 80-room inn was important to attract guests to visit the island, and, ultimately, purchase a homesite in the new Sea Pines Plantation. The first year of the Inn’s existence averaged only two guests per night. Charles was undeterred. He knew that if visitors could spend time here, they would fall in love with the island – just as he had – and want to make it home.

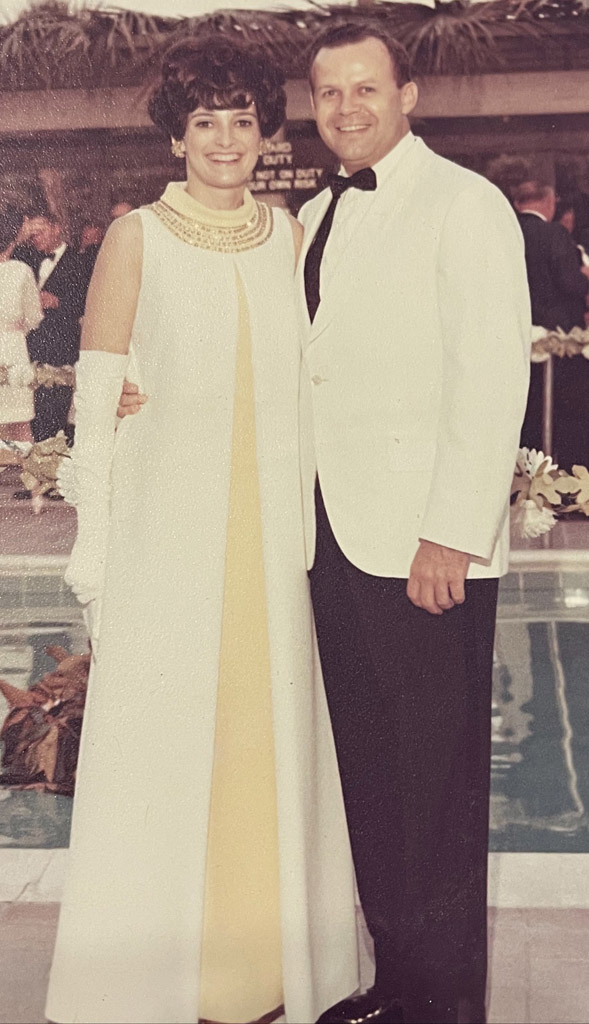

On November 30, 1963, Charles married Mary Stone, whose parents owned Stone Manufacturing Company in Greenville, South Carolina. Mary and Charles were a perfect union. Mary not only supported Charles’ efforts, but she was very involved with the business in the early years, entertaining guests and making them feel welcome.

The Frasers hosted an oyster roast and cocktail party at their home in Sea Pines every Friday night for the next six years in order to welcome new property owners and Inn guests. Mary and Charles were particularly focused on helping the new residents get to know one another and fostering a sense of community.

Charles and Mary Fraser at a gala event at the William Hilton Inn, late 1960’s

Charles would make the invitation list and Mary would hand deliver the invitations to the home buyers and guests. They were an incredible team in these efforts, which I believe made all the difference in the very beginning.

Charles had a flair for charm and Mary was the ultimate hostess, handling the details of each party with the given resources of the time, which was not a lot. Imagine having close access to only one grocery store!

Mary had to be creative. She made many trips to Savannah for provisions and party props. Everyone who ever was a passenger in her car knows she made these trips in record time! It helped that the 2,000 guests who attended their wedding had gifted them an abundance of silver serving pieces and trays, which Mary used to dazzling effect.

I am grateful that I had the chance to speak with Mary just a few years ago about these early days. Her passion in explaining to me her amount of involvement in the business was poignant. I was struck by how hard Mary worked to overcome the initial hurdles of living on a barrier island with few conveniences.

During these early years, Charles’ dreams were large but his budget was small. He relied on his sales team to sell a homesite in time to make the company’s payroll. When once he made the mistake of complaining of the financial stress to his father, Gen. Joseph B. Fraser, the General retorted that Charles should sell the Sea Pines Company and go to work for someone else. He reminded Charles of how, during the Depression, he never knew each week if he could make payroll for his employees at his timber company in Liberty County, Georgia.

And that was just the nudge Charles needed to go out and make sales.

All this business went on from his car office before the days of cell phones and instant information from the internet. He hooked up a regular phone to the horn in his car and the horn would sound when a call came in. Imagine doing business while driving along dirt roads – because there was no money for paving them.

Charles raised enough money to build the first golf course in Sea Pines but fell short on funds to build a pro shop. His improvisation skills came into play again when he dreamed up a lean-to with an oyster shell floor to create a temporary pro shop.

One by one, homesites would sell and he would pave more roads. The open-air golf shed gave way to a multifunctioning golf shop and dining area. And then when he had enough funds for his first sales office, Charles hired architect John Wade of Savannah to plan the structure, with plenty of grassy area that would make a great playground.

Even though he was creating a successful resort, Charles’ primary goal was to preserve the natural beauty of the island’s maritime forest by conserving the natural environment. He promised the homeowners that he would permanently set aside 1,200 acres of the land to remain free from development. He was able to reserve 25% of the property.

Mary Fraser regularly visited the Montessori School, bringing new materials for the students

Charles also succeeded financially. “There is no law that says ugliness pays,” he said. “I selected beauty and set out to make it work economically.”

Developing that additional 25% of land could have brought an even greater margin of profit, but Charles wouldn’t have it any other way.

In 1960, there was only one golf course and homesites were selling for $10,000 each.

Fast forward to 1969, when the third course – the famed Harbour Town Golf Links – was built. Homesites increased in value to $65,000 each. Another decade later, homesite prices ballooned to $700,000. These days, homesites sell for millions.

Not only did the success of Sea Pines bolster the economy of the island, but also the whole of Beaufort County. In 1956, Hilton Head real estate property taxes contributed only 1% of the county’s total. Thirty years later, it paid a whopping 75% of the county’s taxes.

Financial success was not all that motivated Charles. He was extremely grateful when he was honored by his peers. Among other honors, he was awarded the Citation of Excellence in Community Planning from the American Institutes of Architects, and the 1985 Urban Land Institute award for Excellence for Large Scale Community planning. In 1997, he received the Order of The Palmetto, South Carolina’s highest civilian honor.

Charles’ new community would not be complete without institutions for learning and churches for people to gather. Charles donated the land for the first private school on the island, Sea Pines Academy, now known as Hilton Head Preparatory School, as well as the land for the first Montessori School on the island, which was started by his wife Mary in 1968.

Along with members of the original Hilton Head Company partners, Charles gave land for numerous churches. Charles and Mary’s daughter, Laura Lawton Fraser, said, “I am convinced that donating the best commercial land he owned back to God was the wisest strategic move he ever made and it was what ensured the success of Sea Pines. All of these donations were done without any tax gains. They are also largely unknown. There are no plaques or monuments recording these gifts. But his gifts reflected his heart.”

Charles envisioned his new development as a resort and he made tremendous strides to place its foundation in the first decade. He dreamed of “something” that would be the heart of the development, so he and Mary had many meaningful conversations about what that would be. They traveled to other communities to get ideas. Nothing seemed to be just right for Sea Pines. Other communities weren’t an island like Hilton Head. Whatever it was to be, it had to be natural for an island.

One day, with all the flair and personality that Charles was known for, he said to Mary, “I’ll build a harbor. A harbor town.”

And Mary said, “That’s it!”

From my desk across the creek, I pause to remember how influential Mary was to Charles in the early days and how much she contributed to the success of Sea Pines. Mary set out to make everyone who came to the island feel at home.

Volunteerism was and still is at the core of the island’s success, and no one exemplified it better than Mary. She didn’t just demonstrate it, she taught all those around her to follow in her footsteps. The strong force of Mary and all the executives’ wives that pressed on in the early days to build what we have today is memorable, noble, and admirable.

Next month we’ll explore more about how the iconic Harbour Town became the heart and soul of Sea Pines, and how the annual PGA Heritage Golf Tournament was born.

Charles Fraser with his daughter, Laura Lawton and beloved Saint Bernard, Cinderella, who is buried in a marked grave at the Fraser Circle in Sea Pines