Published by permission from the Charles E. Fraser Estate, with editorial assistance from Laura Lawton Fraser

I had decided to move “across the creek.” As a nearly five-decade “south-ender,” this came as a surprise to many, including myself. What in the world would make me move to the north end? I don’t know the stores, I don’t know the restaurants.

By now, most of you are laughing at me, I know. It’s silly on a 12-mile-long island to have such anxiety about a mere 10-minute drive. I’m even laughing now, as almost two years have passed since I made the move. But, if you ask long time islanders, it really is a thing.

However, despite my trepidation, when the right property presented itself and it was the right price at the right time, I jumped on it, quickly, and without thinking too much. I’m proud to say that the move across the creek turned out great for me and I absolutely love it. No anxiety needed, and it was time wasted worrying about whether I would be happy.

When my family first moved here in 1975, our decision to buy a home on the south end came with much less worry. Back then, Hilton Head Plantation and Port Royal Plantation existed, but most of the living and doing was on the south end. We lived in Shipyard, close to school and all our friends.

The south end boasts most of the island’s wide beaches, so as the island was being developed, the south end became more accessible to tourism. The north end gated communities leaned towards long-term living, since no short-term rentals were allowed.

It is quite fair to mention that our island could have easily fallen prey to the tacky commercialism of the era if not for the vision, foresight, and intricate planning of developer Charles E. Fraser.

Had Charles not set his creative sights on planning a community where people could live and work and play, all while existing among the natural settings of a tasteful seaside environment, the fate of Hilton Head Island could have been something entirely different. Imagine if this were another oceanside town full of big neon signs, casinos, and high-rise buildings.

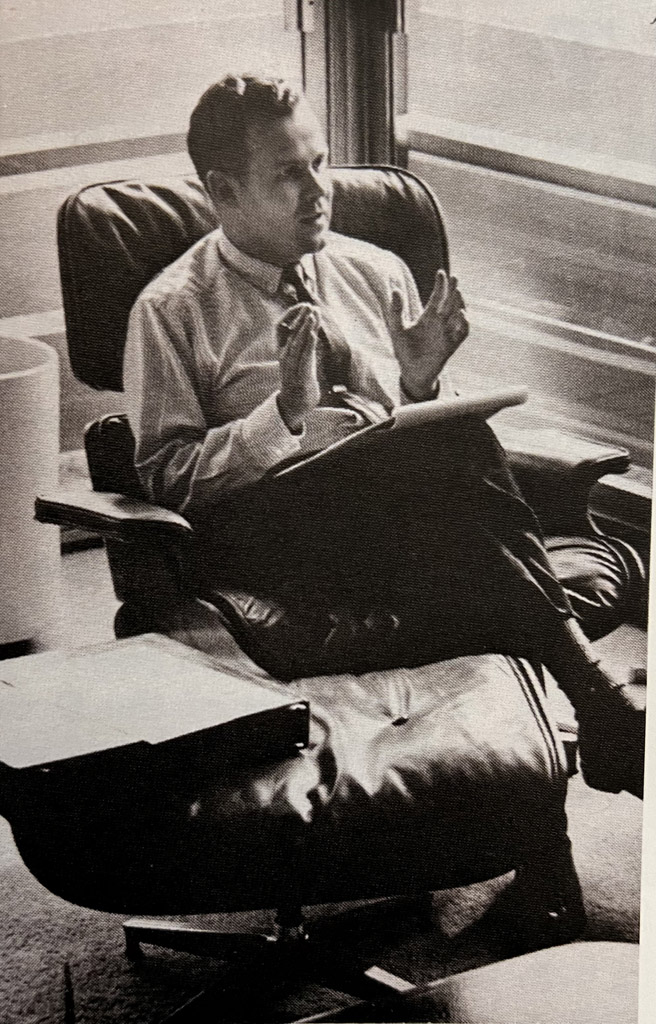

Charles E Fraser in his office, early 1960s

Laura Lawton Fraser, Charles’ youngest daughter, wrote and presented a speech to the Clemson University Masters of Real Estate Class in March 2014. She spoke of the early days of Hilton Head and the events that led her father to create Sea Pines Plantation. Her talk gave an idea of how we avoided being a cut-over timber tract or a glorified Myrtle Beach. Following are some highlights of her topics.

In 1949, a group of lumber associates from Hinesville, Georgia, purchased 20,000 acres of pine forest on the south end of Hilton Head Island for an average of almost $60 an acre. These gentlemen formed the Hilton Head Company to handle the timber operations. These associates were Joseph B. Fraser, Fred C. Hack, Olin T. McIntosh, and C.C. Stebbins. In 1950, logging began and three timber mills were constructed to harvest the timber. At this point, 300 residents lived on the island.

Charles’ brother Joe Fraser spent time working with the timber crews and Charles would come in the summers to join the workforce between his semesters at Yale Law School. He fell in love with the island upon his first visit. It was during these summers that Charles would hop on a tractor when not working and explore the land, dreaming about it and planning how to develop it. At 21, Charles had already painted the picture in his mind of what he wanted to do with the land that is now Sea Pines. This presented a dilemma for the young man who was passionate about law, but his heart had been captured by the island. Now his future was being pulled in two different directions.

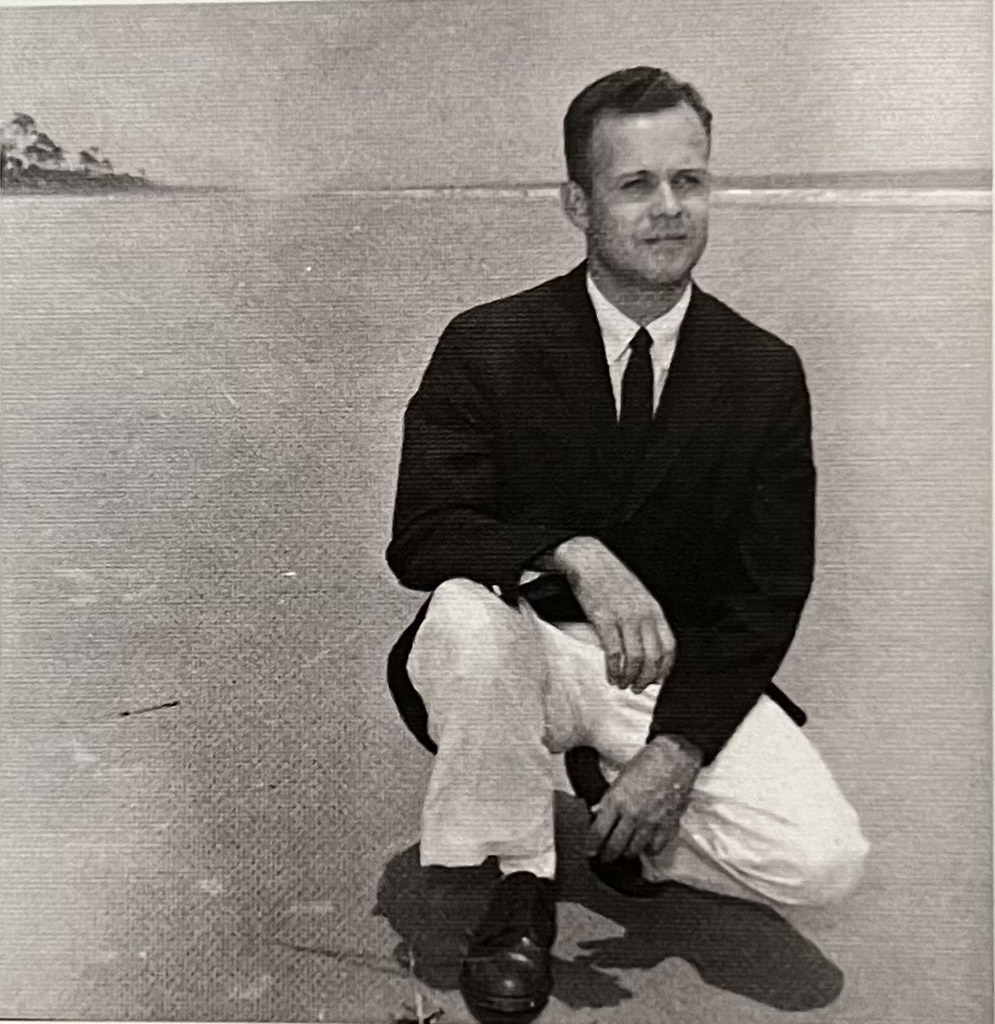

In the 1950s, Sea Pines Plantation was used as the private hunting grounds of Maj. General J. B. Fraser and his sons. (Back row, left to right): Reuben Clark, Sr., President of the Savannah Bank and Trust Company; Thomas M. Johnson, Sr., President of Johnson, Lane Space and Company; and J.D. Holt. First row left to right: Attorney John B Miller, 27-year-old Charles E. Fraser, and Attorney Robert C. Norman.

Charles knew he could develop the island in an environmentally sensitive and profitable way. He was plagued by the idea that an island as beautiful as Hilton Head could become another Atlantic City or any other of a thousand tasteless coastal strip developments that had popped up along the eastern seaboard. But he didn’t have the answer as to how to get it done his way.

The solution came while at Yale, when he heard a professor teach a course on Land Use Planning and Allocations by Private Agreement. This was the answer to his dilemma! It was basically the legal concept of putting restrictions into deeds that permanently controlled how land could be developed and re-developed.

After a stint in the Air Force during the Korean War, when he was sent to Washington to read documents at the Pentagon, Charles took a job at a law firm in Augusta. One of the principals at the firm told Charles he could tell that though Charles was physically in Augusta, his heart was in Hilton Head.

A young Charles E. Fraser surveys the beach on Hilton Head Island, early 1960s

Seeing how torn Charles was between his love of practicing law and his passion for the remote Carolina barrier island, the elder man advised Charles to take a sabbatical from the law firm and go spend two years trying to make his dream come true. “If you fail, no one will judge you harshly as a 25-year-old,” he said.

Charles took this advice and left the firm. He later reflected that it was just the impetus he needed to convert him from practicing law to becoming a developer instead.

What an important turn of events that decision was for all of us who live here now. As I sit at my desk in my home across the creek, I think that whoever the principal was at the law firm deserves a lot of credit here. Had he not encouraged Charles to give his ideas a try, I can only imagine what would have transpired.

Charles began his work on developing the island with no development experience and very little money. There were five huge obstacles: 1. There was no bridge to the island; 2. There were no landscape architecture firms in the South; 3. He didn’t own the land; 4. He didn’t have money; and 5. In the summer the island was a mosquito nesting ground akin to a malarial swamp.

All of these are daunting issues, but Charles, being the perpetual optimist, set forward anyway. He would not be deterred.

The course of the next several years eternalized Charles’ dream as, one by one, he found creative and purposeful solutions for all the many roadblocks that came his way.

Next month we’ll look at another decade of the life and work of Charles E. Fraser and explore how marrying Mary Stone Fraser influenced the development of Sea Pines.