It’s hard to believe that it has been 12 years since Cranford Hollow (Cranford & Sons at the time) exploded on the Lowcountry stage with their fiery self-titled debut. That 2012 album (later re-released as The Crescent Beach Sessions) hit with a sonic fury, the audio equivalent of sucking down Jameson right from the bottle with the other fist raised high in the air.

It not only introduced one of the area’s most sought-after local acts, it kicked off an unprecedented streak that saw the band put out new original music nearly every year that followed. On an island that probably had more of a reputation for toe-tapping covers than original sounds, Cranford Hollow managed to not just continue releasing music, but to evolve their original Southern Stomp ethos into something more diverse.

In 2013, their (technically) second self-titled album saw them adding horns to the mix with songs like “5th Ave.” The next year’s Spanish Moss and Smoke saw the band exploring the country music side of its origins, from the overtly country fried “Life I’m Living” to the Zydeco flavor of “Waitin’ on That Train.”

With St. Telluride, they emerged as balladeers, with tracks that showcased their lyrical ability. Color/Sound/Renew/Revive offered up tantalizing hints of a band poised to truly experiment with the sound that had brought them fame.

And then, nothing.

That last album dropped in 2016. The breakneck pace of releasing new music, touring relentlessly, and headlining late-night gigs and festivals all over the Lowcountry had finally caught up to one of the hardest-working bands in the business.

“The band sort of went on an unknown hiatus after (Color/Sound/Renew/Revive). We were super burned out from seven years of doing 225 shows a year,” said front man John Cranford. “We didn’t play much. We didn’t even really get together to jam. But we were always working on ideas, whether that be lyrics or music.”

From seven years of steady playing, Cranford Hollow went to seven years apart. Cranford, bassist Phil Sirmans, violinist Eric Reid, and drummer Randy Rockalotta would drift in and out of each other’s orbits, occasionally playing the odd gig with one another. But otherwise, it was more or less a chance for them all to reconnect with their own music.

Then, one unremarkable day just like any other, they decided the hiatus was over.

The tall ceilings made for an interesting sound acoustically, especially for the drums. The band placed a stereo mic (an old Sony formerly used for broadcast TV and film) up in the arch of the ceiling to capture the sound.

“I said we need to put something out, so we rented a cabin … to lock ourselves in for a week and just jam,” Cranford said. “That was really just the purpose. Playing in the band with your brothers for all that time, you start to miss it. You get lonesome for the guys and the music. We didn’t have lyrical ideas. It was all music based.”

They spent a week in Big Thunder, the A-frame cabin featured on the album’s cover, exploring why they had enjoyed playing together in the first place. Everyone brought something to the session, whether it was a loose, fleeting idea for a song, a few cobbled together notes, or the roughest notion of a finished song.

Then they all took turns helping coax those diamonds from the earth (with help from what Cranford calls a “wild card in the recording process,” a 1972 Fender Rhodes electric piano borrowed from fellow island musical icon Martin Lesch.

“You play piano totally differently than you do guitar or banjo, so a lot of stuff came from there,” Cranford said. “We tracked and tracked and tracked … there’s a ton of things we recorded from that week.”

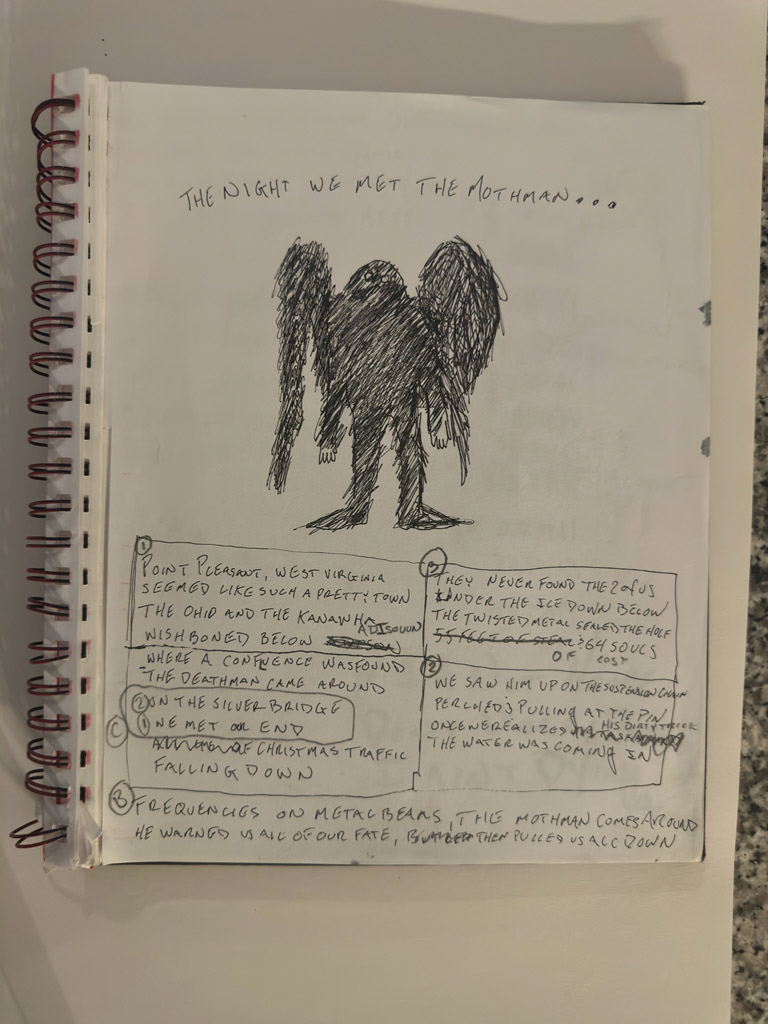

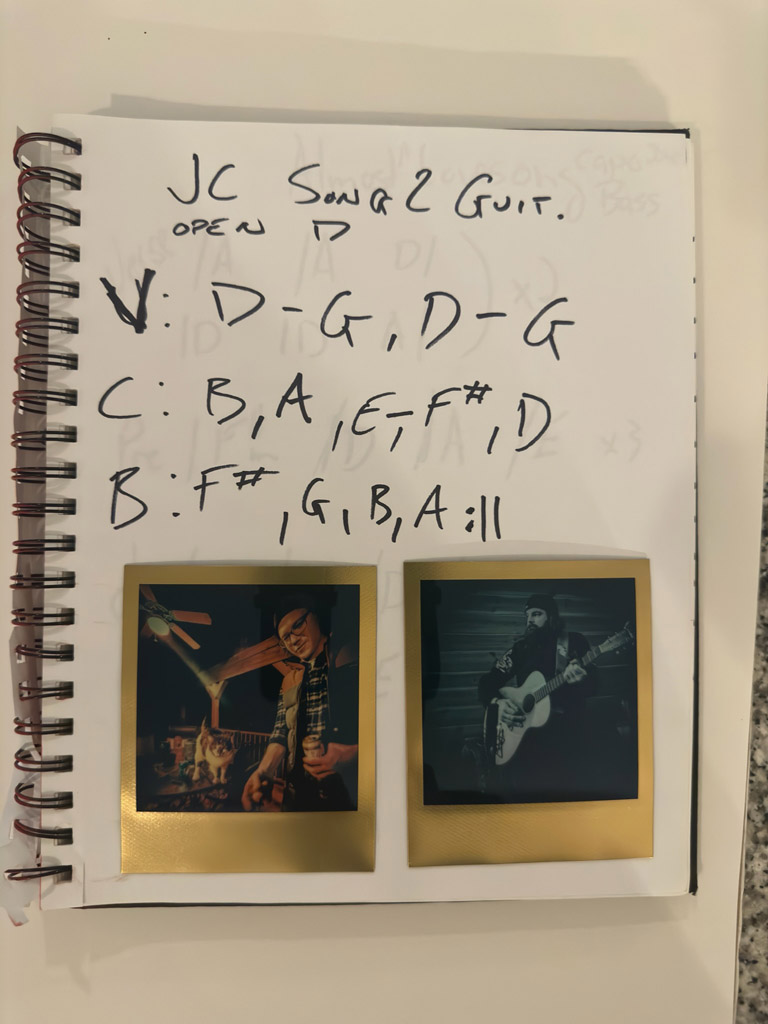

Mothman was the only song the band had written prior to making the trek up to Zirconia, and they only had the lyrics completed. The music would come later.

They returned from Big Thunder with the sound, but not the words. That’s where celebrated producer Will Snyder came in.

“We actually flew him in from L.A. to help us out with it, spending another month tracking on top of what we’d already done,” Cranford said. “The nice thing about having Will involved is, he can really tailor a song to make it more conducive to lyric writing. … He does a great job of hearing what needs to be filled into a space and lets you push the envelope as far as you want.”

To master the new album, the band turned to a new influence – Sterling Sounds’ Idania Valencia. “There’s a lot of masculinity when you have a bunch of dudes in a room. So, when we went to master it, we had a lightning bolt idea to get a feminine touch in there to balance it out,” Cranford said. “We got it back and just said, ‘Holy smokes, this sounds like a real record.’ Obviously Will did an excellent job, but her contribution really tied it together.”

The result was Sounds from Big Thunder, an album that finally delivers on the transformative era their early discography hinted at. But rather than experiment with new sounds or instrumentation, the album sees them rediscovering what set their sound apart in the first place – Reid’s fiddle breezing over top of a bluesy/country/rock soundtrack of Rockalotta’s crisp drumming, Sirman’s songwriting, and Cranford’s gravelly voice.

Built with the old-school mentality of an album, carrying the listener along on a journey whose complexion changes with each track, it’s a musical manifesto of a band that spent more than a decade earning their spot as elder statesmen.

“We’ve been doing this for so long and we’re getting older. Randy turned 50 last year and I’m pushing 40. We’re all either married or in long-term partnerships,” Cranford said. “This album is a lot about getting older and that interpretation of what we’ve been through as a band, as brothers, as husbands … I think there’s a lot of emotion on these tunes.”

Put simply, if Cranford Hollow’s sound prior to their seven-year hiatus was like a swig of Irish whiskey, Sounds from Big Thunder is like a smooth glass of high-end bourbon.

“It’s hard to be with the same people doing the same thing, basically living in a van 200 days out of the year, and we really needed a break from each other,” Cranford said. “This record, this process, relit that fire.”