Lawson Lowrey can’t remember a time when he didn’t want to fly a plane. His family gave him flight lessons when he was 15, and that’s when Lowrey first realized the immense responsibility of piloting an aircraft.

“I took lessons, and being a pilot was a dream, but I was just too unfocused to follow through at that point in life,” said the now 49-year-old Lowrey. “Now, I get it. Learning the mechanics of an aircraft is hundreds of hours of work; that alone is not for everybody. But beyond that, it’s about embracing that you’re responsible for other lives above all else, to make sure the aircraft is safe and your flying is technically flawless. You have to be ready to earn the right to live that dream.”

After a brief flirtation with the family business, Lowrey went into selling medical device equipment—first stents and balloons, now pacemakers. Fifteen years ago, he became friends with a medical practice manager in Georgia, who heard of his passion for flight and had the perfect mentor for him: her husband.

Dr. Rusty Harrington, known to his buddies as “Doc,” has been flying planes for 50 years. His father took him to the airport to watch planes, and when Dad was learning to fly in a 1946 fixed wing single engine Piper, an itty bitty Rusty was behind the pilot seat in the baggage compartment.

“You just couldn’t keep me out of planes. It’s always been a passion,” said the now 63-year-old Harrington, who first flew a plane at age 13. “I was lucky that the learning felt natural. The responsibility behind flying was an earned honor. My dad ingrained that in me.”

His father soon after bought a third-share interest in a Navion, the Cadillac of fixed-wing aircraft built by North American Aviation, the same company that produced the P-51 Mustang during World War II.

“He later was given the plane by a friend who owed him money, and that started a lifelong love affair with this plane,” Harrington said. “It’s been fun to pass that love on to guys like Lawson.”

When the two connected four years ago, Lowrey was once again committed to getting his pilot’s license. Just like Doc’s father had done for him, Lowrey was sharing his love of flying with his teenage son, Maximilian. He was determined to get his license and buy a plane to share with Maximilian.

“I work 24/7 in this job, and this dream was my outlet,” Lowrey said. “These planes, this hobby, it’s not the elitist thing that is the stereotype. You can buy a plane for less than you pay for a Range Rover, a boat or an RV. These classic planes, you can get one for less than you pay for a Silverado. They are masterfully built, will last you a century if you take care of them. I’ve been driving boats since I was 12. But the mechanics of flying and flight safety, it’s thousands of hours of learning.”

Doc told Lowrey to get back to flight school, get hundreds of hours in as pilot, get his solo flying license, and buy a Cessna—the Honda Civic of airplanes—a popular starter plane in wide production with good resale value.

Lowrey at first decided to buy a slicker, sexier plane, but later ended up buying the Cessna, where he went to work showing Doc just how committed he was to earn his new friend’s tutelage.

That’s when Harrington introduced him to a friend, Bud Brown, a Skyhawk pilot in Vietnam, who is now the president of the Southeastern Navion Group, enthusiasts of the plane that went out of production more than 50 years ago after producing just 2,500 total planes.

Now 80, Brown was ready to part ways with his aerial beauty. Harrington convinced Brown that Lowrey was worthy of purchasing his 1948 Navion A.

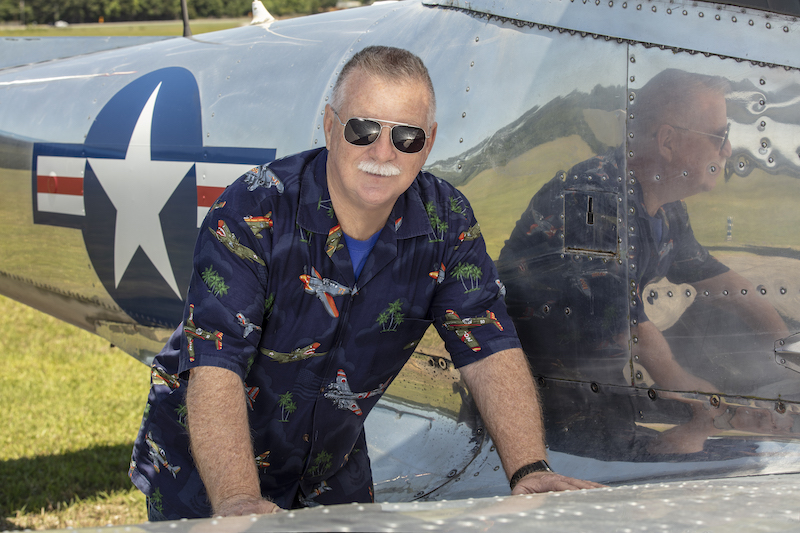

“Doc told me I’ll never need another plane, and he was right. This plane is a gorgeous machine. It’s an honor to carry on the legacy that Bud established with this plane,” Lowrey said of the four-seater Navion.

While not flown in combat, the plane is adorned with the VA-23 emblem of the Black Knights, Brown’s Navy attack squadron. The plane’s 311 insignia matches the plane he flew in combat.

“His wingman in the Black Knights has a 312 plane. He passed away,” Lowrey said. “I’ve been asked to fly with that plane, but I was not in the military. I would never dishonor the service these men gave to our country.”

Lowrey often makes the 12-minute flight from Hilton Head to Statesboro, Ga. to meet Harrington at his airport hangar that houses the E.R. doctor’s budding collection of planes.

There’s “Triple 6,” a 1955 Navion named for the plane’s N91666 tail number, a five-seater that Lowrey calls “Rusty’s hoss.” The plane is actually Harrington’s son’s, acquired in 2012.

“That thing is not a slow plane; it is simply magnificent. It’s a five-seater that will fly you anywhere,” Lowrey said, admiring his friend’s plane.

There’s the “Millennium Falcon,” a fellow 1948 Navion A that Doc bought in 2002 and has rebuilt the engine since to make it one of the fastest planes among his SNAG group. Harrington also has a Rangemaster, an early-1960s revised version of the Navion, and another Navion he’s fixing up to sell.

Then there’s the family prize, the 1946 Piper he and his doctor brother, Bob, learned to fly on. The family sold the plane after their father passed away, but Bob reacquired the plane 30 years ago, and the brothers have spent the time ever since restoring it to its past glory.

“It’s something special to keep this in the family—so many memories, and it’s still such a gorgeous flight to this day,” Harrington said of the family heirloom.

Doc has countless airplane parts in the hangar. The vice president of the American Navion Society is also a master mechanic known in the Navion community for his skills in rebuilding and fabricating long-out-of-circulation Navion parts.

“I have always had this mechanical aptitude, blessed with it. I took an engineering test in high school and did so well, Georgia Tech wanted me to finish school with them,” he said. “I just hated school, so I threw the letter away. But I went back after getting married and starting a family, passed my mechanic’s test, got my college degree and my medical degree. And I’ve been acquiring knowledge all along. There are always things to learn with these planes.”

Lowrey said flying has become an integral part of his life and that he treasures the mentoring and friendship he has built with Harrington. “God had his hand in my friendship with Rusty. He doesn’t tell me what I should do up there. He tells me mistakes he’s made that he’s learned from and that’s just invaluable,” Lowrey said. “You have to be willing to listen to be a pilot. He’s told me many times, ‘There are old pilots, and there are bold pilots. But there are no old, bold pilots.’”

There’s a fine line between confident and cocky, and pilots are masters at never crossing that line. “Cockiness kills, period,” Lowrey said. “When I’m in the air, it just takes my breath away every time. I’m proud to have earned this convenience—to be able to fly to Atlanta in an hour, to Florida in 90 minutes, to dream up a trip and just get in and fly. It’s easily my greatest life accomplishment.”

He said seeing his son achieve his aerial dream is equally rewarding. Maximilian, a student at The Citadel training to become a Marine pilot, was ready as a teen for the full gamut of accountability that comes with flying. He said the feeling you get on takeoffs and the responsibility of piloting the plane is unparalleled.

“It is super addictive. I want to be in the air all the time,” Maximilian said. “To share this with my dad and Doc is a gift I take very seriously. I am always learning, always striving to master skills.”

While the Lowreys have hundreds of hours of flight time under their belts, Doc has flown 4,600 flight hours and close to 4,700 total flights—most of them done over the past 20 years, many commuting between his Statesboro, Ga. home and his medical practice in La Grange, Ala.

“I’ve flown as far as California. We visit our four kids and 10 grandkids. We’ve flown over Yellowstone, past Mount Rushmore, to Canada, the Gulf of Mexico, over two oceans. We’re going to spearfish in South Dakota next month. My wife and I fly to Florida or Atlanta or Charleston for dinner,” Harrington said. “I fly every chance I get. I’ve seen parts of the country few will get to see, thanks to these planes. It’s just an amazing life.”